As mentioned in the introduction of general concepts, JavaScript as a language provides some basic classes for regularly returning tasks. Let’s learn how to use them before writing own classes.

Can you recall the lessons learned from the last section?

What is a class, what is it used for, what is it made of?

1st: Now what you use

At first, to reference a class, you obviously need to know it’s name. Because you need this name to create an instance object from it.

Important base classes will be introduced to you by teachers or colleagues. During your professional career you will explore more frameworks and libraries and their documentation, to learn about their provides classes and their use.

2nd: Construction

In the world of object oriented programming, the creation of instance object is usually done by calling a so called constructor. In JavaScript you use the dedicated keyword new inside a variable definition instead.

A constructor is a special reserved-named method of a class. As a design choice of the classes writer, it can have none to many parameters, you may need to know to create an instance object.

blank constructor

To use any previously defined class, we have to create an instance (object) of that class. In code this looks like this:

var objectInstance = new PreDefinedClass();

executing this line, leads to the reservation of memory to keep the state of objectInstance and execution the method constructor (if there is one)

parametric constructors

If the classes constructor defined parameters, you need to pass them within the brackets after the classname

var objectInstance = new ClassWithConstructorParams(10,'a');

Usually you will find some documentation of the class author telling you, if you need parameters. e.g. this one.

vocab and limits

To have a function or method with the same name but different sets of parameters is called overloading in object-oriented programming languages. JavaScript does not support this concept, but overrides re-defined functions and methods instead. Calls will execute the latest evaluated definition of a function/method

The behavior that “fakes” overloading can be achieved by offering a method with the maximum of parameters analyzing which of them were passed to the function/method inside it’s code body.

Every time a function/method is called an arguments object is available inside it’s body. You don’t need to instance it yourself. The arguments object helps you to discover the numbers and types of the parameters given. This could for example look like this:

function welcome(firstname,lastname) {

if(arguments.length ==0) {

console.log("Hi");

}

if(arguments.length == 1) {

console.log("Hi " + firstname);

}

if(arguments.length == 2) {

console.log("Hi " + firstname + " " + lastname);

}

if(arguments.length == 3) {

console.log("Hi " + firstname + " " + lastname +

", " + arguments[2]);

}

}

Lets have a look at the pre-build Date class of JavaScript language. Following the documentation of Date class, we can instance it with several sets of parameters, what feels like an overloaded constructor.

- empty without param: Date()

- this leads to an object representing the current date and time, while executing the statement

- it won’t change after creating, not ticking like the systems clock

- up to 7 numeric parameters: Date(2019,12,19,9,30,0,0)

- this instances an object with a representation of 19th of December 2019, 9:30 am

- less parameters set less parts of the date

- 3 parameters will only set year, month, day and leave time at 0:00:00 am

- one string parameter: Date(‘December 19, 2019 09:30:00’)

- the constructor will try to parse the string in several ways, and if successful create a date representing the given literal. If not, the created object will be invalid

Your task! #1

- open a node.js terminal.

- create several variables for instance objects from the Date object

- use different sets of parameters as mentioned above

- you can use your birthday for example

- log the variables with console.log()

Now you know, how to instance objects from classes, let’s use the instances now.

3rd: (a) use methods on instances

After instancing the object from class, you can calls methods of the object. This is done with the objects name followed by the dot (.) symbol and the methods name and brackets. The brackets are obligatory, even if the method has no parameters, to distinct the call from reading an attribute.

var birthday = new Date('1981-11-27');

var weekdayOfBirth = birthday.getDay();

Hint: the getDay()-method of Date class returns a number from 0 to 6 reflecting the day of the week, sunday=0, monday=1, thuesday=2 … saturday=6

3rd: (b) use of static methods directly from classes

There are a plenty of cases, where a developer writes add methods to classes, that should be available without instancing an object from a class.

- the method is possibly not dependent from any state-information of an object, but only from parameter values

So called ‘static’ methods are not called from an object instance (aka variable names), but from the class itself. A prominent example for these are all the calculation-methods of the build in JavaScript class Math. For example you can retrieve the square root of a number with the static method sqrt() of the Math class.

> var baseValue = 16; > var squareRoot = Math.sqrt(baseValue); > console.log(squareRoot); 16

You can find a complete list of Math classes static methods on several sources like: Mozilla MDN – Math

Your Task! #2

- open a node.js terminal

- define 2 variables for base and exponent and assign numbers to them (e.g. 2 or 10)

- use the static method .pow() of class Math to calculate the power

- write the result to console.log()

4th: use of attributes

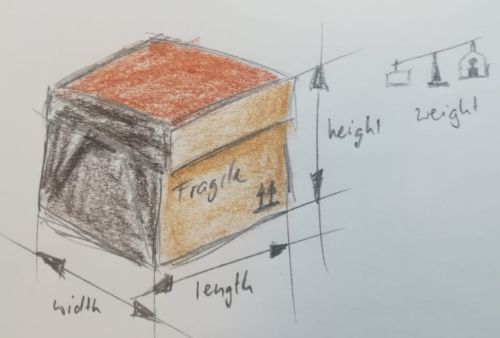

Like methods you can just define variables in your class to preserve an objects state. Usually this is done in the constructor, in the same step like the initialization of the values. Let’s look at this code-example of a class Box representing package boxes in a logistics context, where the measurement, material and weight are important things to know.

Your task!: #3

- open a node.js terminal and write the following given code, representing our transport box

class Box {

constructor (width, length, height, weight) {

this.width = width;

this.length = length;

this.height = height;

this.weight = weight;

}

}

- now create an instance object of this box with new keyword

var mybox = new Box(10, 5, 2, 2.5);

We can read and write the attributes of mybox by using the objects name followed by a dot (.) and the attribute name.

- play around with setting new values to the attributes

- do some calculations with values read from the objects attribute set

> mybox.width = 7.5; > var volume = mybox.width * mybox.length * mybox.height; > console.log(volume); [output:] 75

no static attributes, but kind of

In Math class, we saw earlier, their are a couple of constants defined, that can be read from Math class directly, without instancing a variable. Those constants behave like static attributes. But JavaScript again does not provide such a concept, but ways to provide the same use and feel.

The magic lays in the use of static get and set methods, we will see later. But just for using them without deeper knowledge. These examples work “like” static attributes from the Math class:

> var euler = Math.E; > console.log(euler); [output:] 2.718281828459045 > console.log(Math.PI); [output:] 3.141592653589793

At this point, you know how to call methods and access attributes of objects and static methods directly from classes. Let’s continue writing your own classes.